Running of the Bulls in Pamplona: A Personal Story from the San Fermín Festival.

First-hand account, safety insights, and a cultural revelation.

Years ago, I found myself at 6:00 am on cobblestones older than America, surrounded by 2,000 strangers in white clothing, about to run with six fighting bulls and nine steers through medieval Pamplona. I was only able to run about 100 meters of the 875-meter course, but looking back now, I see how that experience informs how I understand cultural travel, and why superficial tourism never satisfies sophisticated travelers.

This Article is Part 1 of Our Complete San Fermin Festival Cultural Travel Series:

Part 1: Running of the Bulls in Pamplona: A Personal Story from the San Fermín Festival

First-hand account, safety insights, and a cultural revelation. (YOU ARE HERE)

Part 2: How to Travel to the San Fermín Festival: Your Complete Planning Guide for Pamplona

Where to stay, what to expect, and how to experience San Fermín respectfully.

Part 3: Bullfighting and Tourism: Understanding Ethics, Spanish Perspectives, and Responsible Travel

A nuanced look at bullfighting’s legacy, evolving views, and ethical alternatives for travelers.

Note: Some links in this series are to books and other products that we recommend on Amazon. We may earn a sales commission from Amazon without affecting the price you might pay.

The San Fermín Festival begins as the streets of Pamplona overflow with energy and tradition. Locals and visitors pack the main square, dressed in white with red scarves, raising them high as the Chupinazo rocket launches and confetti fills the sky.

This week, the city of Pamplona comes alive with the San Fermín Festival, a centerpiece of Spain’s 2025 bullfighting season and one of the most iconic traditions in Navarre.

The thunder of hooves on ancient cobblestones has echoed through Pamplona for nearly a thousand years. The ritual of bullfighting itself stretches back even further. These traditions are often misunderstood by the uninitiated, romanticized by Hemingway in the early 20th century, condemned by many as animal cruelty in the 21st century, yet still recognized by all as steeped in identity, myth, and meaning.

At Cosmopolitours, we believe that participating in traditional festivals—when approached with respect and an open mind—is one of the most powerful ways to connect with a culture. These events aren’t performances; they are living expressions of heritage, pride, and continuity. To be welcomed into them, even briefly, is a privilege we hold sacred.

Years ago, I ran with the bulls in Pamplona. For me, el encierro (as the event is called in Spanish) was just a few intense minutes of adrenaline and chaos. But it left a mark that still shapes how I travel and how I design trips for our clients. I believe that experiential cultural immersion can change your life, and always for the better. I’m not talking about “living like a local” or checking off a bucket list. I’m talking about understanding the stories behind these events by truly feeling them.

So let’s tell the story…

What Is the San Fermín Festival and Why Do People Run with the Bulls?

Held each July 6th-14th in Pamplona, the San Fermín Festival is a religious event dating to the 16th century that honors the city’s patron saint, San Fermín. It includes rituals like fireworks, Catholic processions, masses, feasts, bullfights, and most famously, the adrenaline-charged encierro, the Running of the Bulls, which I did myself in my 20s, once only.

Ernest Hemingway immortalized the San Fermín festival for international audiences in his 1926 novel The Sun Also Rises, where he described the bull run as “a spectacle of panic and grace.” His depiction of the Running of the Bulls in Pamplona, and the characters drawn to it, gave Pamplona global notoriety and a mystique that still draws adventurers, spectators, and literary pilgrims to this day.

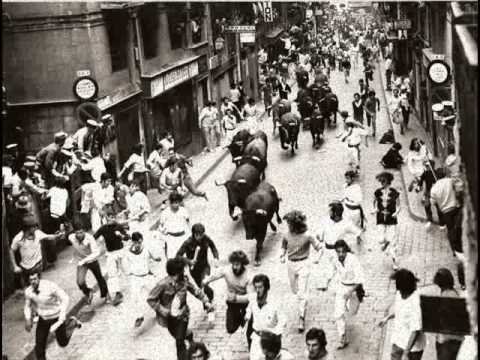

A historic photo from the late 20th century captures the raw intensity and enduring tradition of the encierro in Pamplona’s old town during the San Fermín Festival.

Hemingway’s 1926 novel The Sun Also Rises introduced the world to Pamplona’s San Fermín Festival and forever linked the Running of the Bulls with literary legend.

What Is It Like to Run with the Bulls in Pamplona?

This is how I remember it…

At around 6:00 am, on the third day of the San Fermín Festival, my traveling buddies and I hauled ourselves out of our cheapo hotel beds and dressed in the white shirts and pants we had procured the previous day from what was a combination hardware store, convenience mart, and low budget purveyor of menswear. The key accessories are the red pañuelo (neckerchief) and the red faja (sash) secured around the waist and tied-off in a slip knot, not for quick release in case it catches on something (like a bull’s horn).

Thanks to the blessings of youth, we were unfazed that we’d gotten only a couple of hours of sleep, having spent the previous day and night drinking and carousing anywhere that would have us.

How Many People Run with the Bulls in Pamplona Each Year?

Before 7:00 am, we approached the crowd of mozos (the runners), more than 2,000 men, and a handful of women, near the starting point of the run, the Corrales de Santo Domingo, at the bottom of the street of the same name. There were police everywhere directing spectators back and mozos forward.

Moving through the crowded street, a small, stout older man smacked me on the leg with a rolled-up newspaper. He had an electrified shock of grey hair. “For de bool” he said indicating his satchel full of carefully compactly rolled newspapers. He demonstrated their use by smacking another of my buddies on the shoulder. Then he hit himself on the forehead with it, repeating, “para los toros, bool”. We bought newspaper bull-smackers from him at 10 pesetas each. Before he moved on, the old made a sign of the cross big enough to bless us all, “Que Diós os bendiga, extranjeros”- “May God bless you, foreigners.” Done with us, he turned and smacked someone else with a newspaper, repeating his pitch, hawking his wares.

Armed now with our newspapers, we filtered into the front of the assembled mozos, wired on fear and visions of glory. Still more runners took their places ahead of us until my dudes and I were effectively engulfed in a sea of white dotted with red. We nervously shuffled our feet, pretending to stretch and warm up. We had drunkenly surveyed the route the night before, theorizing how we might conquer the event, but in the golden early morning light, the realization dawned that all our talk of strategies and methods had zero relation to the reality we were facing.

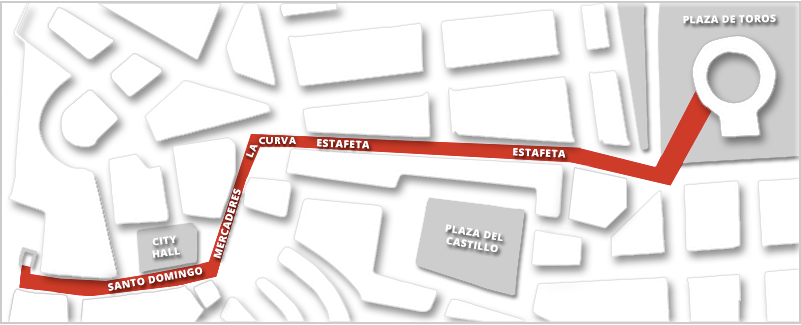

The crowd of mozos was much bigger than we had thought. The uphill grade at the beginning of the course now looked steeper than it had during our reconnaissance yesterday. Alongside the uphill stretch, the placement of so many first aid stations, each with gloved emergency workers at the ready, now seemed more threatening rather than sensible precautions. The 90-degree right turn onto Estafeta seemed foreboding, a drop-off into the abyss. Every fighter has a plan until they take that first punch.

The red pañuelo is more than a symbol—it’s a rite of passage worn by all who take part in Pamplona’s San Fermín Festival.

Why Do People Run with the Bulls in Spain?

The Spaniards were much more serious than us extranjeros. While we were smiling and gregarious to cover our anxiety, they were stoic. For us it was thrill-seeking fun. For the Spanish mozos it was serious business. They knew so much we didn’t about the dangers that lay ahead, the histories of mozos gored and maimed along the straights and corners of the route, how few of us (less than 10%) would actually make it into the bull ring at the end of the course. The Spanish run with the bulls intentionally, in the face of their knowledge of the risks. Some run for heritage to prove themselves against the previous generations of their family who had also run. One Spaniard we met said his uncle was gored 12 years before at the Curva Telefónica, so he was running to avenge him and vindicate the family honor. Compared to us, the Spaniards were courageous. We were uninformed, foolhardy, and reckless.

During our carousing the night before, my buddies and I had asked a few Spaniards whether our sneakers were suited to the cobblestone streets (spoiler alert: nope – best to wear very soft-soled shoes). The response of the guys we asked was the same each time: “It doesn’t matter.” We took that to mean our shoes were adequate. Later, I understood what they really meant: “it doesn’t matter – for you.”

The encierro route runs 875 meters through the historic center of Pamplona—from Santo Domingo to the Plaza de Toros—passing through some of the city’s most iconic streets.

How Does the Running of the Bulls Start Each Morning?

The sound of so many chattering people -runners, spectators, first responders- echoed loudly off the buildings and cobblestone streets as we awaited our fates. Until an eerie hush fell, spreading out to envelope the whole of Pamplona’s historic core. It was close now.

A skyrocket launched from the faraway bullring streaked into the sky and popped. It was 8:00 am, the beginning of el encierro, when the bulls were released from the corals behind us. The crowd of mozos behind us lurched forward, pushing us all forward like a wave. We were walking at first, then jogging until the shouts of the spectators behind us made it clear: the bulls were loose. When we heard the clatter of hooves on stone, we started running.

From that moment on, it’s a blur. Men running with newspaper rolls in hand. Teenage Spaniards pushing past, shouting indiscernibly. I found I was alternately boxed in by the other runners or getting dragged along by their tide. My buddies and I hung together. Then bulls were right there. Fight or flight, lizard-brain panic set in.

The first black fighting bull or toro bravo, and a brown and white steer, charged past us on the right. We moved to the left. We didn’t know it at the time, but that was lucky for us – because the bulls favor their right, you want to stay to their left.

I was the slowest of my group of buddies, falling behind them. Though fit, I was almost immediately winded and panting-adrenaline takes your breath away. One of our group, a young Irishman called Timothy O’Reilly, shifted into another gear and dodged through the crowd, leaving us behind. I plowed uphill along the Cuesta de Santo Domingo, the rest of my friends now a dozen meters ahead of me. I called out to them, but I was on my own.

I heard the clanging of a cowbell as a brown and white steer roughly butted me aside as he passed. How did he get there? A startled runner in front of me glanced back and immediately tripped. A Spaniard had told us the night before to never look back, now I knew why. I managed to skip over the downed mozo, but couldn’t resist the urge to glance back – pandemonium and a free-running bull about 15 meters behind.

I will swear to my dying day that somehow me and that bull made eye contact. He angled his very pointy horns at me. I knew he was coming, and that I was done.

Seconds from danger—runners scramble to safety as a bull charges toward the fence during the San Fermín Festival in Pamplona.

How Can You Stay Safe Running with the Bulls in Pamplona?

I headed to the barriers to my left, but so did the dozen other mozos around me. They were leaping onto the barrier and heaving themselves over, but they blocked my way. Desperate now, I scrambled forward some meters ahead to an available bit of barrier and hurled myself onto it, trying to get over to safety, but not quite getting there.

Luckily, mercifully, two Spanish men purposefully purchased atop the barrier grabbed my wrists and hauled me over. I managed to land on my feet thanks to kind souls there propping me up. The people on that bit of sidewalk hugged me, congratulated me. Apparently, because I had touched a steer, I had acquitted myself well, though really he had touched me. A first aid worker buzzed around me, checking that I was in one piece and not bleeding. “Estupendo!” she said, planting a peck on my cheek before checking on another mozo who had just come over the barrier.

I had survived. I looked back down the hill: I had made it about 100 meters from where we started. Good enough, I figured. I turned for the tapas bar near our cheapo hotel that we had adopted as our headquarters and meeting point. Then my other buddies – less Timothy O’Reilly – ambled up grinning ear-to-ear. They had jumped out about ten or so meters beyond me chased by the same bull as me. One of the dudes told me that he had looked back and saw the black bull barely miss my ankles as I got lifted over the barricade. Flying on adrenaline, it didn’t really register that I had narrowly averted a possibly life-changing injury, or worse.

Experience the adrenaline of the San Fermín Festival in motion—watch as runners and bulls race through the historic streets of Pamplona during the encierro.

What Happens at the End of the Bull Run in Pamplona?

We crowded around a small table at our tapas bar headquarters, chomping Iberian ham sandwiches, papas bravas, and croquetas, while watching the live TV feed of the mozos and toros in the bullring at the end of the course. As the adrenaline wore off, thoughts of mortality began filtering in, not only for us, but also for the bulls. The chaos in the bull ring on TV started seeming less heroic and more pointless, folly.

Time passed. We began worrying about our friend Timothy O’Reilly. He wasn’t in the bull ring as far as we could see on TV. Had he gotten hurt? We considered going out to look for him after our next beer, discussing who should remain behind to man headquarters. Then, on our third beer, Tim stepped inside, his once white clothes soiled with dirt, a few streams of blood flowing down his left forearm from a gauze-covered scraped elbow. He saw us, smiled at 1000 megawatts, and raised his arms in victory like Rocky Balboa.

Here’s the guy who ran with the bulls—a fearless, hairy young global traveler already chasing stories beyond borders—long before becoming a cultural travel expert.

Is Running with the Bulls Worth the Risk?

We valiant fools had run with the bulls and lived to tell the story, as I am telling you now. Most of us agreed that we wouldn’t do it again. One and done, we said. Timothy O’Reilly, tending to his elbow with a moist napkin, cocked his head, disagreeing. He wanted to try again, now that he knew the course, he could make it into the bull ring. He did try again the next morning. He didn’t make it as far as his first go and was happy to retire as a mozo two and done.

Our consensus was that we were each happy to have run an encierro, and that it was worth the effort for us to have done so. Now, many years later, I’m still glad that I did it, and feel like it gives me meaningful insight into Spanish culture.

It took me years to fully grasp what those Spaniards meant when they told us our shoes didn’t matter. Back then, I thought they were dismissing the question. But what they were really saying was: you don’t understand—and maybe you won’t.

This tradition wasn’t built for us. It doesn’t exist for our entertainment or approval. It’s part of something older, deeper, and wholly theirs. And that realization, that we were outsiders brushing up against something sacred, was the moment I began to understand what cultural travel really is. Not about blending in. Not about thrill-seeking. But about learning to stand humbly at the edge of someone else’s world —and listen.

Coming up in Part 2 of this series, I’ll share Cosmopolitours’ best pro tips for anyone planning their own trip to experience the San Fermín Festival in Pamplona. Of course, nothing compares to traveling with Cosmopolitours. We’ve spent years cultivating insider connections, expert hosts, and experiences you simply won’t find online. That’s what we do. But we also know not everyone will join us, so we’re happy to share a bit of our secret sauce to help you travel smarter.

Finally, in Part 3 of this series, we’ll explore how the Spanish people feel about their bullfighting traditions, what’s changing, what’s enduring, and how travelers can engage thoughtfully.

Anthony Rubenstein

Tony is the co-founder of Cosmopolitours. Son of an art historian, Tony was exposed to international cultural travel from a very young age. He speaks three languages, has visitied over 80 countries, and lived full time in 5 of them. When he's not planning trips-of-a-lifetime for our clients, you'll find him playing with his Rhodesian Ridgebacks, Tado and Mali.